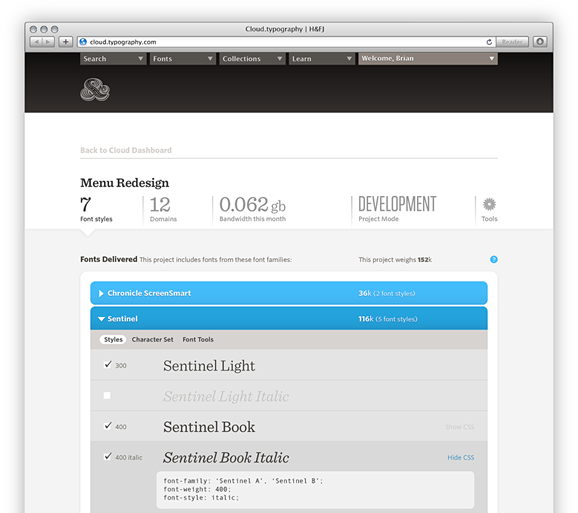

The true cost of H&FJ’s web font platform

Chris Bowler from the Campaign Monitor team has written an interesting comparison between Typekit and Hoefler and Frere-Jones’ new cloud.typography web font service. If you’ve been sizing up clouds.typography, or didn’t know that H&FJ has (finally) launched their much anticipated web font platform, go read his post.

One thing that Chris didn’t touch on, but I think is relevant to the comparison, is that H&FJ’s annual subscription fees don’t actually give you access to their full range of fonts, just five font families:

Join Cloud.typography and get your first five webfont packages FREE

If you want access to more than five families then any additional fonts need to be purchased separately – currently H&FJ’s popular Gotham family costs $149 for a web font license, or $299 for a web and desktop license.